Dear Visitor,

I welcome you to this non-profit, educational page. Here you will read about different aspects of the history and culture of that part of our globe which is known variously as Bharatvarsha, Hindostan or India. My approach of looking at history is that of a rationalist and humanist. As my aim is to spread awareness about history and culture, you may freely download this page, print it, link it up from your site, or mirror it at any server. Enjoy the infotainment laid out for you at this site. I also look forward to your valuable suggestions and feedback. Happy viewing.

Author |

|

Hindu History

The Origins of Our Caste System in Vedic Times - Brahmins

_____________________

By Sudheer Birodkar

_____________________________

Table of Contents

_________________________________________________

Caste is an institution which is truely Hindu (Indian) in character. So much so that even the Concise Oxford Dictionary defines it as, Hindu hereditary class, with members socially equal, united in religion, and usually following same trades, having no social intercourse with persons of other castes. The word caste itself is derived from the Portuguese word 'Casta' which means pure or chaste. In the Indian lexion we refer to caste by the words 'Varna' meaning colour and 'Jati' which is derived from the root syllable 'Ja' which means 'to be born'. But why does the caste system that prevails mainly among the

Hindus, also exists in a subconscious manner amongst

Muslims in India (Pakistan and Bangla Desh) as also among the Christians and Sikhs in India?

| For a long time people from some castes were not allowed entry into temples - A deformity created by the caste system.

Seen here is the Jagannath Temple at Puri in eastern India which is one the holiest of Hindu temples and is considered to be one of the four dhams. Adi Shankara also established a Mutt here of which a Jagadguru is in charge. The other three mutts being at Dwarka (in the west), Kanchi (in the South) and Badrinath (in the north) |

Casteism amongst Muslims (in Pakistan and India)

Despite their conversion to Islam; Pakistani Muslims still refer to themselves as Jats, Gujjars,

Rajputs, etc. This is especially so during match-making in an arranged Nikah (marriage). One instance of the visibility of casteist feelings among Pakistanis is the reference Benazir Bhutto makes in her book

'Daughter of the East', when she says, "In my veins runs the blood of a Wadhera".

Wadheras are a Rajput clan from Punjab and Sindh.

Caste also exists among Bangla-Deshi Muslims.

Casteism amongst Indian Christians

Indian Christians also are not free of caste. Goans and East

Indian Christians, still refer to

themselves as Bamons (Brahmins), Bhandaris, Kolis, Prabhus, etc.

Casteism amongst Sikhs

The Sikhs too refer to themselves as Jat Sikhs, Mazabhi Sikhs, Ramgarhia

Sikhs. Jat Sikhs profess surnames like Chauhan (Jagjit Singh Chauhan), Dhillon (Ganga Singh Dhillon), Arora (Jagjit Singh Arora), Oberoi, Saini, etc., that

display caste backgrounds.Ramgarhias and Mazhabis have generally no surnames as

Sikh tradition recommends.

Why is Casteism an Indelible Pan-Indian (and Pakistani) Reality?

Why is Caste so indelible that it can remain among communities who

now profess religions that decry caste distinctions?

Why is it that among Hindus caste is such a sticky factor that it refuses

to die despite the Constitution of India's ban of the system?

Why do we

still have a Mandalization of Indian Politics?

Why many

centuries after their conversion to Islam and Christianity do Muslims

and Christians still subconsciously (and at times openly) observe the caste system they inherited from their

Hindu ancestors?

Why is Casteism is today still a living, rather festering, practice which continues to plague our 20th century Indian society?

Time and again our newspapers carry reports about caste wars in various parts of our country. While reading about Parliamentary news in newspapers, we come across references to the Jat Lobby, Maratha Lobby, Rajput Lobby, Brahmin Lobby, Dalit Lobby OBC Lobby, etc., which brings to the fore the fact that even at the highest level of our country's democratic institutions, caste as a factor is still a living one. And this brought to be so as in the electoral strategies of political parties we hear of caste-based vote banks, caste politics, caste equations in voting patterns, caste-based reserved constituencies, caste based job reservations (that have existed since independence and have been further articulated by the Mandal Commission), ad nauseam.

All this along with the

recurring caste carnages and the ongoing caste politics are a

constant reminder to us Indians that caste and casteism which we

have inherited from our history are still active and alive

around us.

| According to one hypothesis, the origin of the clergy in India goes back to the days when humans learnt to ignite fire through friction. Initially the fire must have been obtained from an already burning source like forest fires. In these circumstances, before the days of ignition the task of tending the fire was very crucial. The function of tending the fire became a specialised one which begun to be passed from

father to son and this select group came to be called

Agni-hotras i.e. 'preservers of fire'. As they tended to the

fire they also roasted and later cooked food for the entire

tribe. In Vedic literature Agni - fire has been referred to as an eater of dead flesh (Kravyad). Fire also served as a formidable weapon against wild animals and other tribes.

Fire was then, as it still is, an object of worship as the

tribal peoples had seen fire as a powerful destructive medium in

forest fires and volcanic eruptions. But after its domestication, fire spelt prosperity for the nomadic people. Prosperity in the form of warmth from the cold climate, protection from wild beasts, better food by roasting the flesh of the hunted animals, etc. The domestication of fire had provided a gravitating nucleus for the collective life of the tribe (Gana). Hence it could easily become an object of worship. When the nomadic Aryans had progressed towards settled civilized life the Central Fireplace (Yagna) no longer remained the gravitating nucleus of their daily life. But their social memory continued to be ruled by the past reality. As to what the tribal Aryans originally did around this central fireplace can be guessed from the original Yagna rituals which today are kept alive in the Yagnas as performed

by Sadhus (i.e. ascetics and hermits). The Yagna Ritual Re-creates all Aspects of Primitive Tribal Collective Life One Contemporary writer describes this Yagna ritual as follows:

" The Yagna ritual " ... " is a process in which almost all primitive social life has to be recreated. You

have to produce fire by friction of two pieces of wood, to build a cottage where no iron is used but only specific wood and grass, to milk cows, make curds, pound corn with stone (not even a stone mill), boil and cook it, ..." This description brings out the fine semblance between the original Yagna ritual and the function of cooking for a tribal household. In the public Yagnas, like the Rajasuya and Ashwamedha Yagna that were sponsored in later ages by kings, many alterations and refinements were introduced but the original primitive features stuck fast. These royal Yagnas involved the coming together of innumerable Brahmins, the consigning to the central fire, generous quantities of sandalwood, camphor, ghee (clarified butter), grains, and even sacrificial animals and birds. All this corresponds to the central fireplace theory as the origin of the Yagna. This lingering social memory perpetuated the practice of having the central fire, which in the changed circumstances became a ritualised form of worship. The recollection of the extinct past fermented ideas that invocation of the fire would again spell wealth and prosperity as it had after its domestication. In the Yagna ritual of later days up to our own age, the hymns sung in the Vedic days are recited, the collective social life is reconstructed in a ritualised manner with the fond hope that all this would spell prosperity for the performers of the Yagna. But the Agni-hotras, who conducted the Yagnas by virtue of being placed in between the tribe and the domesticated fire, also performed the functions like making offerings to the fire and invoking it to spell prosperity for the tribe, victory in war,

etc., apart from roasting and later cooking which was their primary function. These

Agni-hotras were the prototype of the Brahmin caste of today. In addition to this the hereditary monopoly over the cooking function in Vedic times also gave this section the priestly

functions of invoking the fire-god in favour of the tribe. Thus they came to be looked upon as representatives of God, whose

word carried divine sanction. This being so they also came to acquire the exclusive right of learning (and writing) religious scriptures and

virtually of all knowledge. This was so as, in ancient India, most knowledge had scriptural overtones. Astrology, Astronomy, Mathematics,

Philosophy, linguistics, Law, etc., were the main areas which were developed in ancient India and all these subjects were closely bound up with

religious dogmas. The Agni-hotras "tenderers of the fire" who had become the

clergy (Brahmins), could thus virtually monopolize the areas of acquiring and imparting education, to the exclusion of other castes. |  |

The institution and attitude both of which go into the

making of caste and casteism in today's India remain an

enigmatic one for Indians as also for foreign Indologists. The fact that casteist feelings are still part of our psyche make it all the more relevant that we are informed about how the institution of caste could have come into being.

The Scriptural Explanation

Our scriptures already have an answer to this. The Purusha

Sukta of the Rig Veda says that the four fold division of society into Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas

(warriors), Vaishyas (cultivators) and Shudras (menial

servants) has been created by primeval man 'Purusha'. From

Purusha's brain have emerged the Brahmins, from his forearms

have emerged the kshatriyas from his abdomen have emerged the Vaishyas and from

his feet have emerged the Shudras.

But to examine how the institution of caste could have

originated alongwith the auxiliary practices of untouchability and

endogamy we will have a peep into the society in which the

composers of the Rig Veda lived some three to four thousand years back.

| Buddha preached against observing caste distinctions. Entry into a Buddhist Stupa (temple) was open to members of all castes, unlike that in the case of many Hindu temples. Seen here is the ornate entrance to the Stupa at Sanchi which is representative of the Maurya and Post-Maurya style of sculpture. This style was to change and become more ornate in the middle ages. |

BRAHMINS - THOSE BAPTISED BY FIRE

Caste is a gift of centuries of history whose origin goes back to 3 or 4 millennia in. It goes back to a past when like all other humans, the tribal Aryans roamed the

plains of Central Asia before reaching India. In the new stone age

these tribals lived in conditions of savagery and barbarism. There obviously

was no room for caste division as each and every able-bodied male member had to) help in

the tribe's only vocation of hunting and gathering the means

of subsistence. This common form of labour is referred to as "Satra" in the Rig Veda. This term which literally means 'a session' is still used to refer to religious activities which involve the collective chanting of slokas (hymns).

Agni-hotras the 'preservers of fire'

But with the domestication of fire, things began to

change. It became necessary for some members of the Aryan

tribes to undertake the task of tending the fire and prevent it

from being extinguished. This was before the days when humans learnt to ignite fire through friction. Initially the fire must have been obtained from an already burning source like forest fires.

In these circumstances, before the days of ignition the task of tending the fire was very crucial. The function of tending the fire became a specialised one which begun to be passed from

father to son and this select group came to be called

Agni-hotras i.e. 'preservers of fire'. As they tended to the

fire they also roasted and later cooked food for the entire

tribe.

Fire was then, as it still is, an object of worship as the

tribal peoples had seen fire as a powerful destructive medium in

forest fires and volcanic eruptions. By virtue of being placed

between the tribe and the domesticated fire, this section of the

tribe also performed functions like making offerings to the fire

and invoking it to spell prosperity for the tribe, victory in war,

etc., apart from cooking which was their primary function. These

Agni-hotras were the prototype of the Brahmin caste of today.

The above theory of the origin of the Brahmin caste may seem fantastic and unbelievable, but even today we can see that at our weddings or any other social and religious occasions the cooks are traditionally Brahmins. In some Indian languages the word

for cook is Achari which comes quite close to Acharya meaning a scholar. In Hindi and

Gujarati the word Maharaj is used to address both priests and cooks. Another word which

we use to designate a scholar viz. 'Shastri' also originally meant a wielder of instruments and

not a

scholar according to the; noted Sanskritalogist P.V. Kane.

| Hinduism and the social structure associated with Hindu society represent a combination of extreme philosophical tolerance but cultural intolerance in its social structure. Hence, Hindus welcomed other faiths into India, but observed a strict caste discrimination. Seen here is the Dancing Shiva at Halebid. A creation of medieval Hindu craftsmanship. |

This corollary between cooking and priestly functions may

appear to be outrageous and unreal but the etymological closeness between the

Sanskrit words given below also corroborates this corollary:

| GOD

Shri

Shripati

FAITH

Shradhaa

PRIEST

Shrotriya

Sadhu (ascetic)

Yajakaha

PRAYING

Bhajana

Pathana

|

FOOD

Shri

Shraa, Shraadha (Food offered to

God and departed relatives)

COOK Shrapayati

Siddha

Pachakaha

COOKING ROASTING

Bhajja

Bharjana

Patharaha |

(Source : English-Sanskrit Dictionary by Prof. Vaman Shivram Apte, Mumbai, 1920)

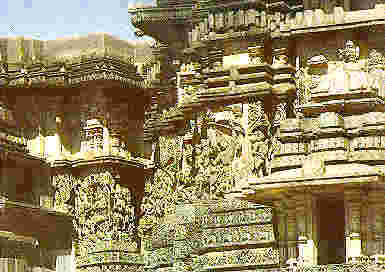

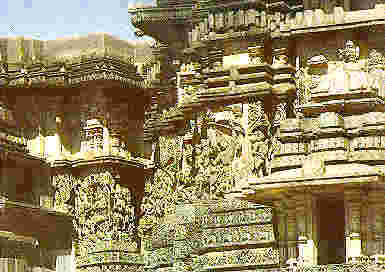

_________________________________________________

| A portion of the Belur temple complex in Karnataka that is famous for its richly intricate carvings. Such carvings were undertaken by skilled craftsmen belonging to the ocupational castes, who were generally not allowed entry into the temples after their construction. |

But this apart, Hindu Shastras (religious texts) have another explanation to offer as per the Holy scriptures ' Brahma Janayate Iti Brahamana' i.e. a Brahmin is a person who has mastered the essence of Brahma (Universe). In the Bhagavad Geeta, Sri Krishna says that the caste divisions have been created by Him.

But if the earlier theory is correct it would justify the origin of Brahmins as a profession of cooks. It is quite possible that this is the explanation behind the Brahmin insistence on cleanliness and

purification which quite logically seem to be a corollary of the culinary profession.

In fact even the Yagna fire sacrifice of today is a ritualization of the original cooking function. During the

Yagna; milk, honey, grains, clarified butter and small figures of animals Pista Pashu) made from wheat

flour have to be offered to the fire. A Yagna is accompanied with mass feeding of people. As mentioned in an earlier chapter

in the original Yagna ritual, which is today observed only by some Sadhus (ascetics) is a process in

which almost all primitive social life has to be recreated. You have to produce fire by friction of two pieces of wood, to build a cottage

where no iron is used but only specific wood and grass, to milk cows, to make curds, pound corn

with stone (not even a stone mill), kill and skin animals, boil and

cook them". This description brings out the close

resemblance between the original Yagna ritual and the function

of cooking on which Brahmin's had come to acquire

hereditary monopoly.

| The Jains were the first sect to break away from Hinduism. They observe the caste distinctions associated with the Hindu social structure, but with less intensity. Seen here are the Arwahi Group of Jain statues near Gwalior date which back to the 9th century. |

But this hereditary monopoly over the cooking function in Vedic times also gave this section the priestly

functions of invoking the fire-god in favour of the tribe. Thus they came to be looked upon as representatives of God, whose

word carried divine sanction. This being so they also came to acquire the exclusive right of learning (and writing) religious scriptures and

virtually of all knowledge. This was so as, in ancient India, most knowledge had scriptural overtones. Astrology, Astronomy, Mathematics,

Philosophy, linguistics, Law, etc., were the main areas which were developed in ancient India and all these subjects were closely bound up with

religious dogmas.

Brahmins who had become the

clergy, could thus virtually monopolize the areas of acquiring and imparting education, to the exclusion of other castes.

There are strict injunctions in our Dharmashastras (legal

literature) against the taking of education by the Shudras.

According to the Dharmashastras, Shudras should remain beyond

earshot when the Vedas are

being recited, the Manusmriti goes a step ahead when it says

that even for an accidental hearing of the Vedic chants a

Shudra's ears should be lopped off. This typifies the

attitude of the Brahmin orthodoxy towards monopolizing

learning and education.

_________________________________________

Now we move on to examine the process that led to the emergence of the Kshatriyas who played an important role, next only to the Brahmins in the caste hierarchy.

_____________________________________________________________

____________________________________View the Table of Contents

_________________________________________________

_______________________________________

_________________________________

With your visit this page has been visited  times since 5th May 1998

times since 5th May 1998